Back in “The Proof is In the Water,” the point was simple: if you want to know what your government is really doing, don’t listen to the speeches, look at the bodies and busted boats floating in our own hemisphere. The new outrage over the Venezuela “drug boat” strike just proves it again.

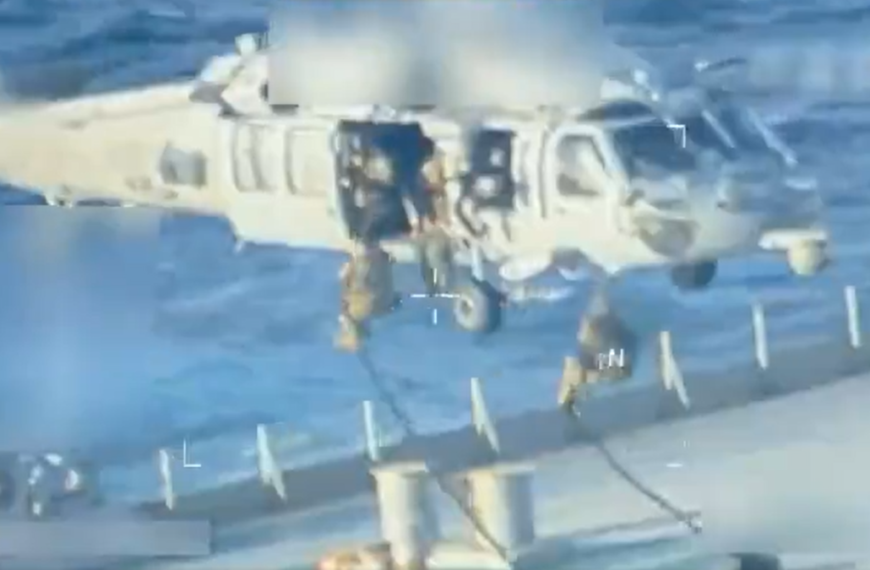

On September 2, a U.S. task force under Operation Southern Spear hit a fast boat the Pentagon says was hauling narcotics out of Venezuela, killing nine men on board and leaving two survivors clinging to the wreckage in the Caribbean. A second strike killed those last two, and that follow‑up is what lit up cable news, law schools, and Congress with the words “war crime.”

A real war on cartels

Here’s the part nobody in D.C. wants to say out loud: this is what a real war on drugs looks like when you finally admit you’re in a war. Operation Southern Spear is not a Coast Guard chase with a bullhorn and a warning shot; it is a full‑scale military campaign that has already destroyed more than twenty alleged drug boats and killed at least eighty‑plus suspected traffickers in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific.

The Trump administration has stopped pretending this is just a police problem and started calling these groups what they functionally are: narco‑terrorists. In the new national security strategy, the Western Hemisphere is elevated to the top priority, and cartels and allied outfits like Tren de Aragua are treated as armed enemies to be “neutralized” with lethal force, under a revived Monroe Doctrine and a “Trump Corollary” that says the United States will dominate the sea lanes in its own neighborhood.

The second strike and the war‑crime talk

The critics hang everything on the second hit. Legal experts and human‑rights groups point out that the laws of war protect shipwreck survivors, and if those last two men were no longer fighting, hitting them again starts to look like targeting people in the water, not a boat in combat. That’s why some lawyers are already arguing this could qualify as a war crime if the survivors weren’t posing a clear threat.

But the people actually responsible for the operation are telling a different story. The White House and the Pentagon say Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth authorized Admiral Frank Bradley to conduct “strikes” plural under Southern Spear, and that Bradley, as mission commander, ordered the second hit because the survivors were still part of an active narco‑terrorist threat, not innocent fishermen. In their framing, you don’t get a “time out” from being a combatant just because the first bomb didn’t kill you.

Protection, not perfection

Is it harsh? Absolutely. But look at what America is actually dealing with at home before pretending this is some abstract law‑school seminar. More than 107,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2023, with roughly 70 percent of those deaths tied to opioids like fentanyl, and fentanyl alone was killing close to 200 people a day. For more than fifty years, politicians have declared a “war on drugs” while overdose numbers climbed and cartels got richer.

If you are going to call it a war, at some point you either fight the people shipping poison into your country like enemies or admit the slogan was always a lie. That doesn’t mean anything goes, and it doesn’t mean there should be no investigations or accountability. It does mean the first duty of the U.S. government is to protect its own people, and that duty includes stopping heavily armed narcotics traffickers long before their product hits American streets.

Drawing the real red line

The honest debate is not “Are these strikes mean?” The honest debate is “Where is the line between tough and lawless when you’re dealing with cartels that use the ocean as a conveyor belt for chemical warfare?” On one side, you have a commander who says he acted within his orders to remove a live threat; on the other, you have critics who act like the only acceptable use of force is a Coast Guard boarding party and a clean chain of custody.

A sane country can hold two thoughts at once: shipwrecked sailors who are genuinely out of the fight should be protected, and narco‑terrorist crews who keep trying to save their cargo and coordinate with their networks are not entitled to a free pass just because they’re wet. The proof, either way, is still in the water—what’s floating there after we act, and what’s floating there when we don’t.